Curt's Story

“It’s just not something you think can happen to you”

Guillain-Barre is a startlingly efficient disease.

“One day you’re walking, and one day you’re not,” said Curt Brown.

Curt, 60, came down with a late-winter respiratory infection. By early February, he began feeling weak and tired. He tried to stand up, but fell. When he realized he couldn’t get up, he yelled for his wife, Cheryl, to dial 911.

“I’m 6’1”. I’m a hunter. I’m healthy,” Curt said. “It’s just not something you think can happen to you.”

Emergency crews transported him to his local hospital. There, they discovered he was the one in 100,000 people to come down the rare disease, where the body’s immune system attacks the nerves.

“I couldn’t breathe, and they rushed into the room,” Curt said. “And then there’s 17 days I don’t remember. They had to trach me and everything.”

With a ventilator breathing for him and a tube supplying nutrients, Curt stabilized enough for his doctors and Cheryl to consider next steps. They chose Select Specialty Hospital – Camp Hill for its expertise in helping medically complex patients begin a recovery.

Curt said the ambulance ride left him a bit surly because “we hit every pot hole on Interstate 81 between here and there.” But when he came through the doors, he recalled feeling instantly at ease. Everyone was so professional, he said, he just knew the rough ride was worth it.

A physician-led team of nurses, therapists, pharmacists, dietitians and aides surged in, conducting assessments that would create the plan to get Curt home.

“When you’re trapped in your body, but your mind is sharp, you just want to get back home,” Curt said.

“I’m a hunter, and a lot of people had goals. Well, my goal was to be ready for hunting season by Oct. 1.”

Pharmacists kept watch on his array of intravenous medications and those needed for his previously diagnosed irregular heartbeat.

Respiratory therapists began working to ease him off the ventilator. They proceeded slowly, because Curt also has a long-standing heart condition. Over the month of March, respiratory therapists progressed him from a special collar that allowed him to breathe more independently to a speaking valve. On March 20, he liberated from the ventilator. Approximately two weeks later, all support ceased and Curt was breathing on his own.

At the same time, physical therapists were working on helping him regain mobility. They assisted him in sitting up in bed, sitting at its edge and moving into a chair. As his breathing improved, so did his ability to participate in therapy.

"There were mornings I didn’t want to get out of bed, I hurt so bad,” he said. “And the physical therapists were like, ‘C’mon, Curt. Just get up for me.’ I realized I was in a place where I couldn’t say no. Which was good because when I went to the rehab unit, I never said no to anything.”

The best part, he said, was that everyone so professional and positive at all times – from housekeepers who greeted him with kind words to nurses, therapists and doctors who rooted for him to succeed.

Dietitians and speech therapists stepped in to help him relearn to swallow, speak and chew. He was able to move from foods the consistency of applesauce to a regular cafeteria tray, though he said is appetite for the things he really enjoys didn’t come back until later.

Just before he left, Curt was able to stand for up to three minutes unassisted and walk up to 80 feet.

He left April 9 for the rehabilitation hospital, where he received three hours of physical and occupational therapy seven days a week.

Before he left, Curt vowed that he’d come back to say thank you when he was well.

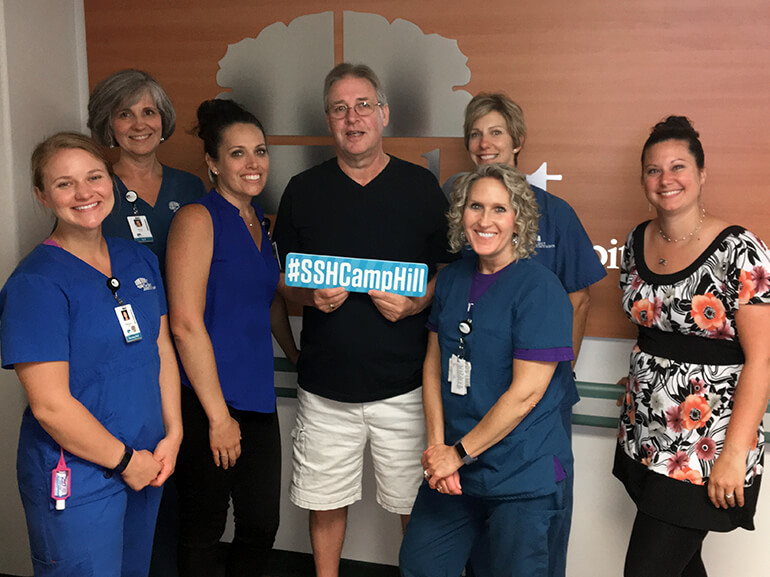

On July 1, he did.

“I said I wasn’t gonna cry, but a couple of the ladies started crying and yeah, I was snifflin’. I walked down the hall, and one of the physical therapists recognized me, then one of the nurse’s aides saw me and she ‘Oh my gosh, it’s you.’ They couldn’t believe it. I didn’t have a cane or anything.”

Curt said he has residual numbness in his feet and hands, but doctors said it can take up to a year to go away.

“I’m walking on my own. I’m tickled to death. Some people take three years (to come back from this), and I crammed everything in in seven months. You either lay in bed and feel sorry for yourself, or get working on what they tell you to do. I know the work I did to get back, not laying in the hospital. Just listen to your team.”